More often than not, interiors - and thereby the women who designed them - were skipped over in history books, which is why we wanted to give Perriand, whose creations presage current conversations about the roles of women and nature in our society, the nod she deserves.

“The key thing for a woman is her freedom, her independence. Being at the top of what she is doing."

Charlotte Perriand (1903 – 1999) was a French architect and designer, and one of the most acclaimed figures to have emerged from the studio environment around Le Corbusier. Working across buildings, interiors and furniture - perhaps most notably chairs - Perriand’s practice evolved radically over her lifetime, shaped by her political views, the turbulence of the mid-20th century and the travels which were forced upon her by those events. Her bold creations caused a sensation. But Le Corbusier took the credit for some of her finest work. Now Charlotte Perriand is finally getting her due.

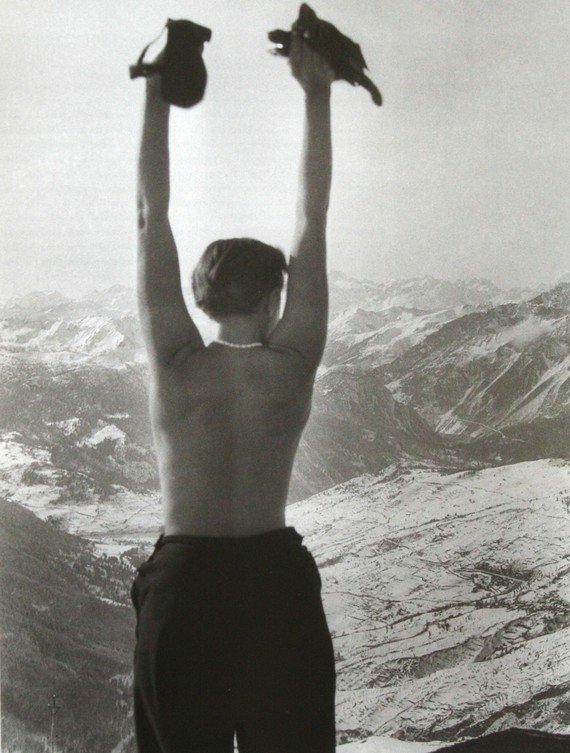

In a prolific career spanning seven decades and three continents, her radical designs were ultimately holistic, all-encompassing blueprints that combined art, nature and an active lifestyle within a single dwelling. There was a profoundly human element to Perriand’s work — she believed good design should be affordable and functional, and blurred the lines between the mechanical world of the indoor and the organic world of the outdoor.

A modernist in the machine age, Perriand didn’t do ‘pretty’. A rebel against her decorative arts training, she didn’t do ‘designer’; and ironically for somebody whose legacy creations include tubular steel chairs and a tilting lounger, she didn’t, in her own mind, do ‘furniture’. She did living spaces and the interior ‘equipment’ that made them habitable.

For her, this equipment – chairs, tables, closets, bookshelves, kitchens and bathrooms – was not a furnishing afterthought. It was an integral part of the architectural process, up there with urban planning, materials science, structural engineering and industrial-scale production. Perriand believed that interior architecture was more than mere decoration, but should be a synthesis of design, architecture and art.

She designed a chaise longue that would have seemed pretty damn racy for women who were still confined to skirts; a ski lodge that looks like a space ship; and an entire resort in Les Arcs, which was imagined to be sympathetic to the surrounding mountains and used innovative modular architecture.

'Her vision was unique and embodied modernity and a forward-facing spirit that continues to shape our society.' |

Perriand inevitably saw a political dimension in architecture – regulating individuals and classes. She paid attention to gender roles and reinvented women’s relation to domestic space. She created open kitchens adjoining living rooms, to literally and symbolically free housewives from a sense of isolation and allow them to take part in the home’s social life and conversations.

She brought down walls and demanded freedom of movement, meaning women were no longer shut off in a kitchen and behind other closed doors, but could remain part of the action (even if they were still doing all the leg work). She always emphasized collective working; sought out new cultural insight and influence in Japan and Vietnam; and considered that the hierarchy of applied arts, fine art and design should be dismantled.

She created furniture which served the everyday life and comfort of a family, put utility and beauty in reach of everybody. Her vision was unique and embodied modernity and a forward-facing spirit that continues to shape our society.

She was an exceptional personality – a brazen, maverick, youthful spirit. A woman committed to leading a veritable evolution, or perhaps more aptly, a revolution. Her keen observation and vision of the world and its cultural and artistic expressions place her at the heart of a new order that introduced new relationships between the arts themselves – from architecture and painting to sculpture – as well as between the world’s most diverse cultures, from Asia (Japan, Vietnam and other countries) to Latin America, notably Brazil. Her work resonated with changes in the social and political order, the evolution of the role of women and changes in attitudes towards urban living. She embodied a transition from 19th century traditions towards the contemporary model of the 20th century.

'Her commitment to conceiving a more egalitarian world has contributed to our ongoing quest for equality of the sexes.' |

|

Her steadfast belief in her own worth is equal to any contemporary feminist trailblazer, and her commitment to conceiving a more egalitarian world has contributed to our ongoing quest for equality of the sexes, particularly in the domestic setting. It is far too easy to try and put a label on Perriand, but she would always loath to define herself, according to her daughter Pernette Perriand-Barsac - finding any single occupation or premise rather reductive. She once stated, “The key thing for a woman is her freedom, her independence. Being at the top of what she is doing.” She made her own rules, and whether or not you impart the F-word, that is inspirational.